The comparative method vs.

the sight-size method

SARA uses the comparative method as the basis of its training. The comparative method involves making measurements primarily using the naked eye, sometimes aided by a pencil, brush or plumb line, and comparing and contrasting these measurements to some other reference or measurement within the subject.

This comparison and contrast helps the artist determine correct proportions and geometric relationships. There is no literal transfer of measurements. Below is an explanation, by SARA’s Director, Hans-Peter Szameit, that compares the comparative method to a popular method of instruction used in most schools of representational art, called “the sight-size method.”

What Sight-size Is

The sight-size method is a popular and commonly used method of teaching students how to draw and paint realistically from life. I was trained to use the sight-size method and subsequently taught it to students in the academy where I received my training, as well as in my own studio and academy. My experience with the sight-size method spans more than a decade, which has given me the opportunity to closely observe and consider both its positive and negative effects upon students. This long experience has led me to gradually change the once high opinion I had of the method, and I now consider it to be quite negative in nearly every respect.

Whether it is called the sight-size method, technique, approach, or system, it is clear that people have very different ideas of what sight-size is, and that has led to a great deal of confusion regarding its definition. Some assert that sight-size has nothing to do with measuring, while others insist that sight-size is defined by the way one measures. In order to have a meaningful discussion, we must define our terms and be clear about what we mean by sight-size. The question of what role measuring has within the definition of sight-size is critical to this discussion. However, in order to proceed, it will be assumed that there is an understanding that sight-size involves mechanical measuring. For those who may not accept this assumption, their doubts are addressed at length in a special section at the end of this essay titled, The Role Measuring Has Within the Definition of Sight-size.

One can find detailed explanations of the sight-size method and how to execute it correctly from various sources on the Internet, but perhaps the best explanation is given by Peter Bougie within the book on Charles Bargue by Gerald M. Ackerman.

Simply stated, the sight-size method positions the model (subject matter) and the artist’s drawing board next to each other so that they can be viewed side-by-side, while the artist stands at a specific distance from them. It is extremely important that the position of the model and the artist’s drawing board (or canvas) always remain exactly the same, as well as the position from which the artist observes them. Therefore, those positions are usually carefully marked using tape or chalk. This exactness is so important, that even the shoes of the artist must be consistent because a difference in the height of the heel can throw off the accuracy of the measuring process. From the artist’s set position, or vantage point, the model and the drawing of the model appear exactly the same size (hence, “sight-size”). This arrangement allows the artist to easily, and mechanically (meaning with the aid of tools other than the artist’s own eyes), compare the model with his own drawing and make corrections. The artist creates a sight-size drawing by taking numerous precise measurements of the model from his set position – using tools such as a plumb line, pencil shaft and mirror – and then transferring those measurements to the drawing board. This transfer of measurements is essential to the sight-size method. By continually taking, transferring and refining measurements, it is possible to create a strikingly accurate copy of the subject as it appears from the artist’s set position.

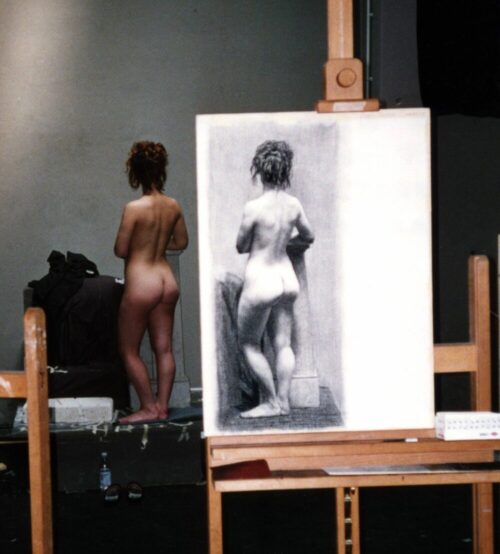

Sight size figure photo

Sight size cast painting

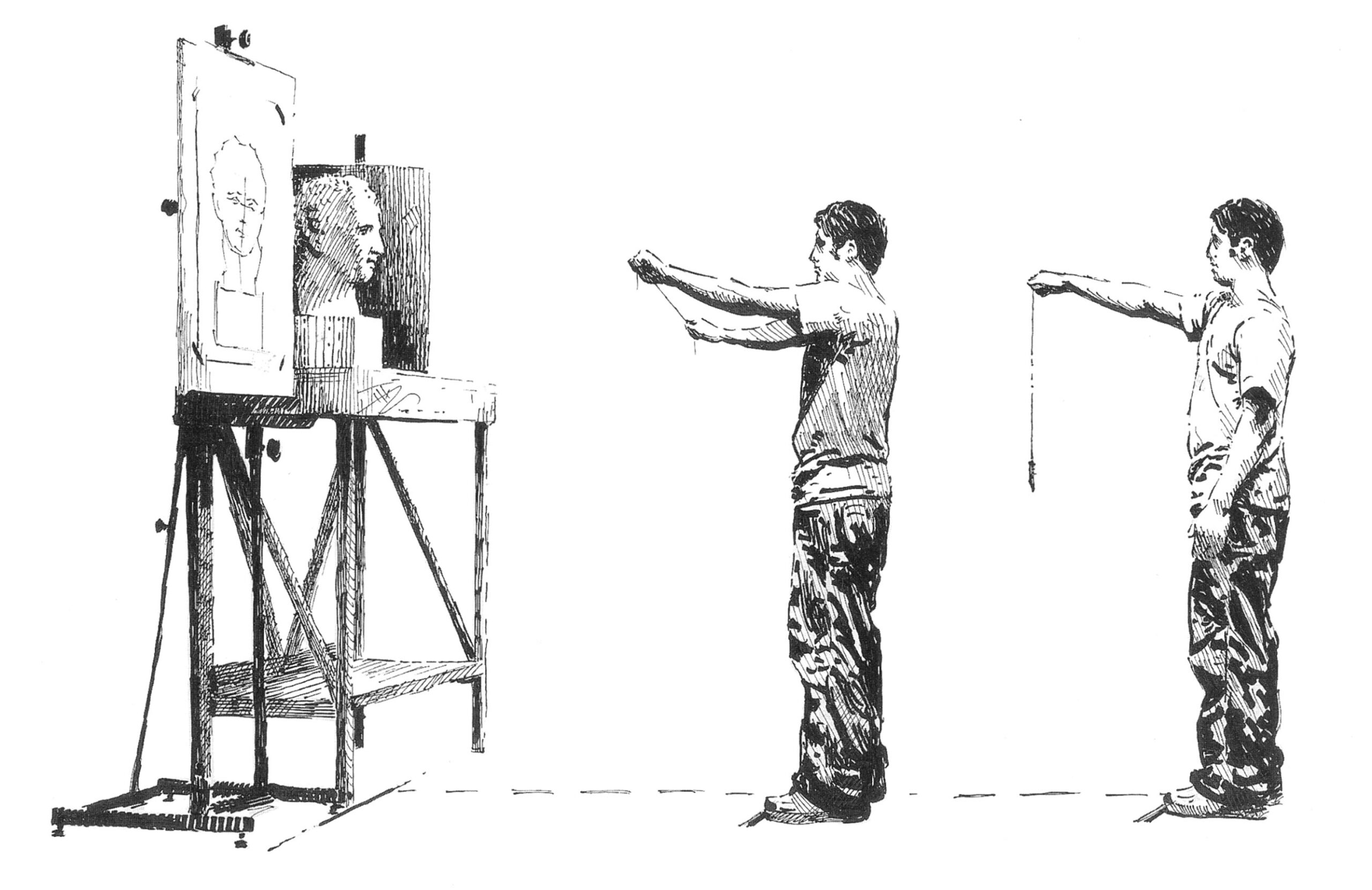

Illustration of the conditions necessary for working sight size drawn, by Graydon Parrish

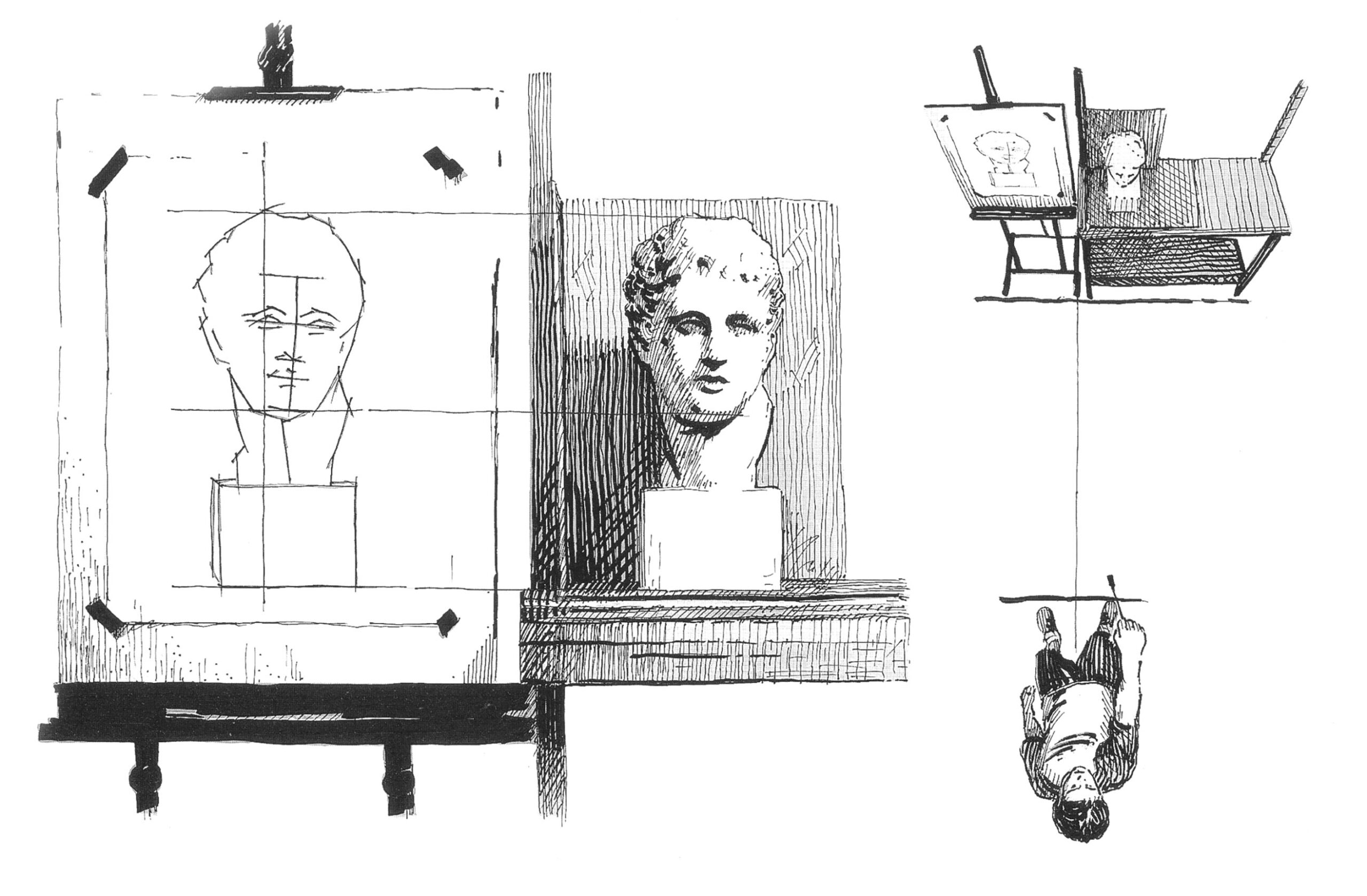

Illustration of the conditions necessary for working sight size drawn, by Graydon Parrish

Why Sight-size Is Not Traditional

Most schools, academies and private ateliers that teach the sight-size method give it credibility by suggesting that it is a traditional method of instruction with a history that stretches back to the renaissance. In fact, this is not the case. The sight-size method is distinctly different from any traditional methods of instruction used prior to the 20th-century. This, in itself, does not speak for or against the method. The sight-size method should be judged on its own merits as a means of instructing students, whether or not it is traditional and supported by a long history. Unfortunately, this is rarely done and instead the method is uncritically accepted, in part, based on the claims of its historical use.

The short essay, “Sight-size, an Historical Overview,”2 by Nicholas Beer, is often referred to in support of the theory that the sight-size method has deep historical roots, even though the essay does not provide any definitive evidence to that end. The essay suggests that the sight-size method has been in use for centuries by citing some examples of past artists who were recorded as having placed their canvases next to their models and then stepping back to compare the results. However, merely setting-up the canvas next to the model, even side-by-side, does not constitute working sight-size unless it also involves taking accurate measurements from a fixed viewing position using tools other than the naked eye, and carefully transferring those measurements to the canvas in order to create an image that is exactly the same size as the subject – and it is precisely these criteria that are consistently missing from any historical references. Painters who placed their canvases next to the model were simply taking advantage of the obvious benefit of being able to see and compare their work next to their subject. Some historical references do hint at similarities, but all fall far short of describing the sight-size method with its inherent emphasis on the mechanical pursuit of precise technical accuracy. Mr. Beer admits as much in his conclusion when he states, “These accounts indicate that sight-size, or an earlier version of the technique, was used by many of the finest portrait painters throughout a period that spanned some four hundred years.” It is clear from the examples in his essay that it was not sight-size at all, but rather something else employed by these painters – what he optimistically calls “an earlier version of the technique”- in circumstances that were, at best, simply reminiscent of the sight-size method.

The art historian, Gerald Ackerman, can only trace the sight-size method as far back as William McGregor Paxton (1869 – 1941)3 who taught the method to his student, R. H. Ives Gammell (1893 – 1981) who in turn taught the method to his students who disseminated it from there – all of which happened within the twentieth century. It is uncertain where Paxton learned the method, or even if he did, because he may have invented it. His teacher, Jean-Léon Gérôme, did not teach using the sight-size method or I am sure Mr. Ackerman, probably the world’s leading expert on Gérôme, would have noted it. Edmund Tarbell, another of Paxton’s teachers, may have been the source, but that too is uncertain.

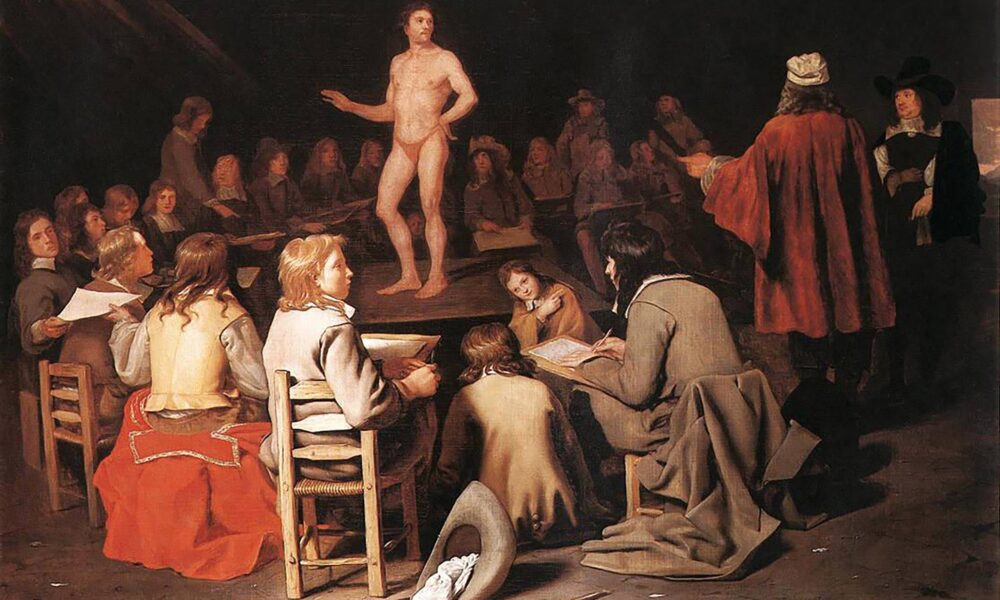

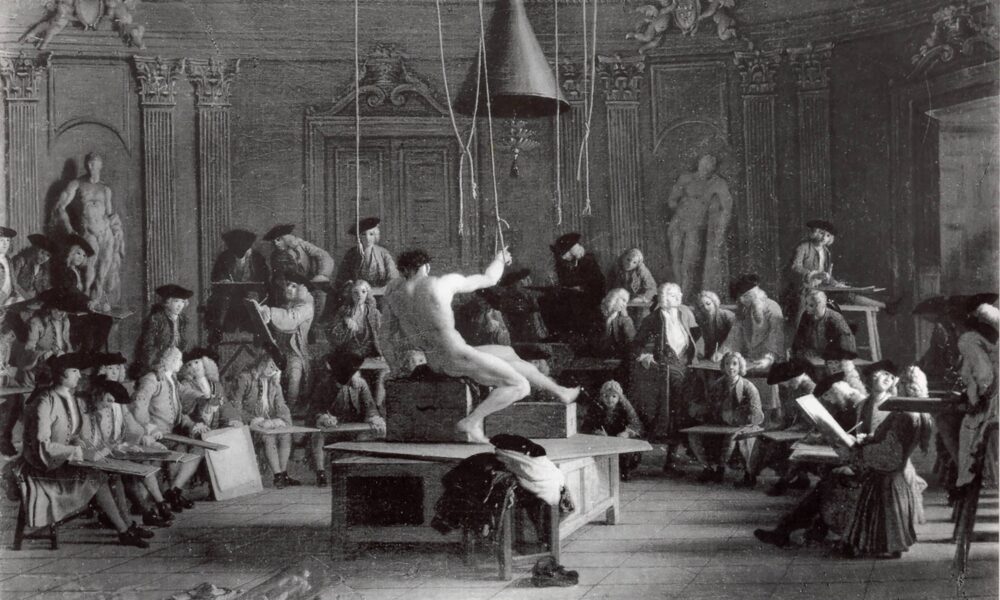

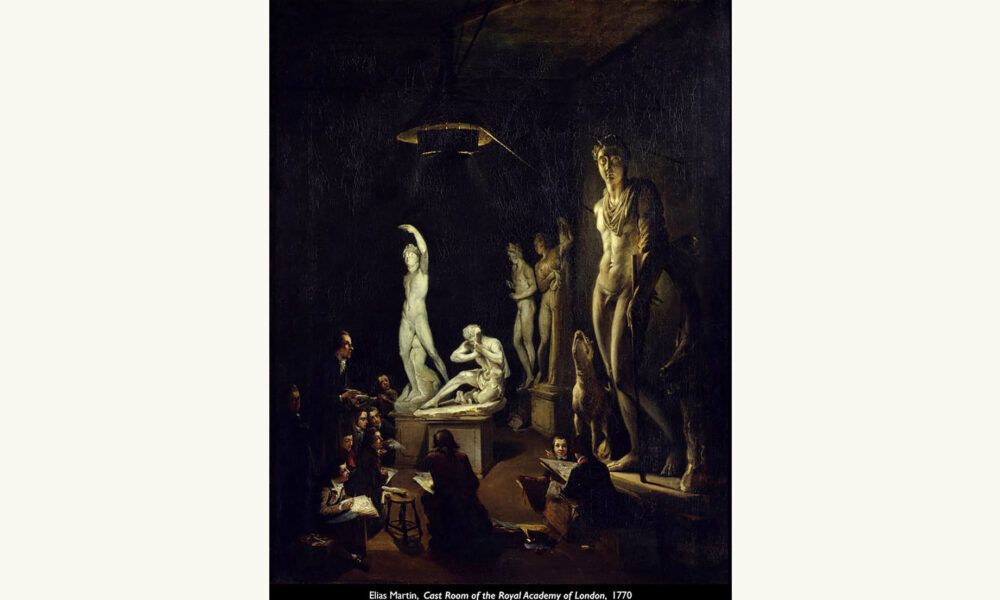

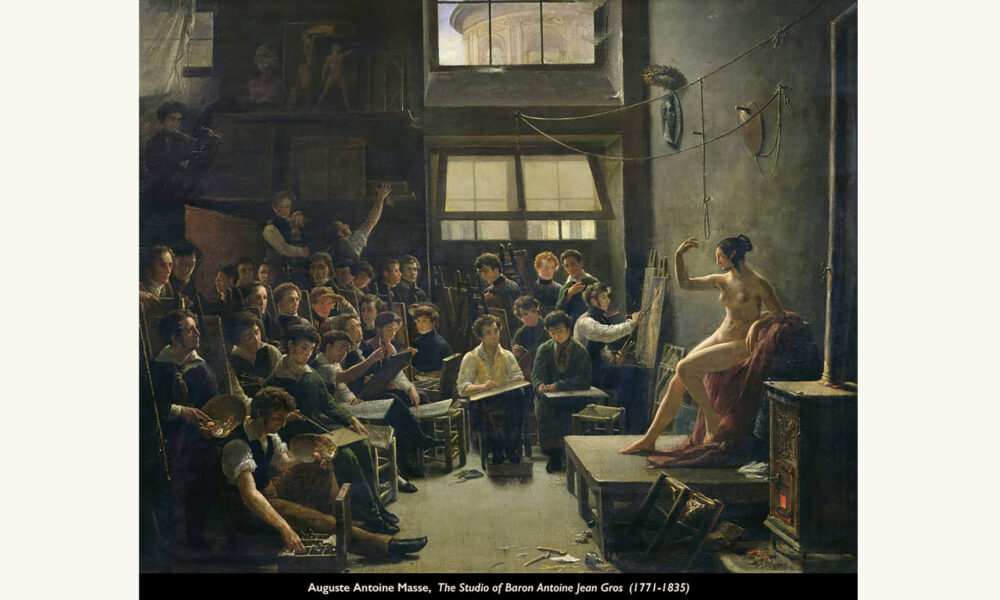

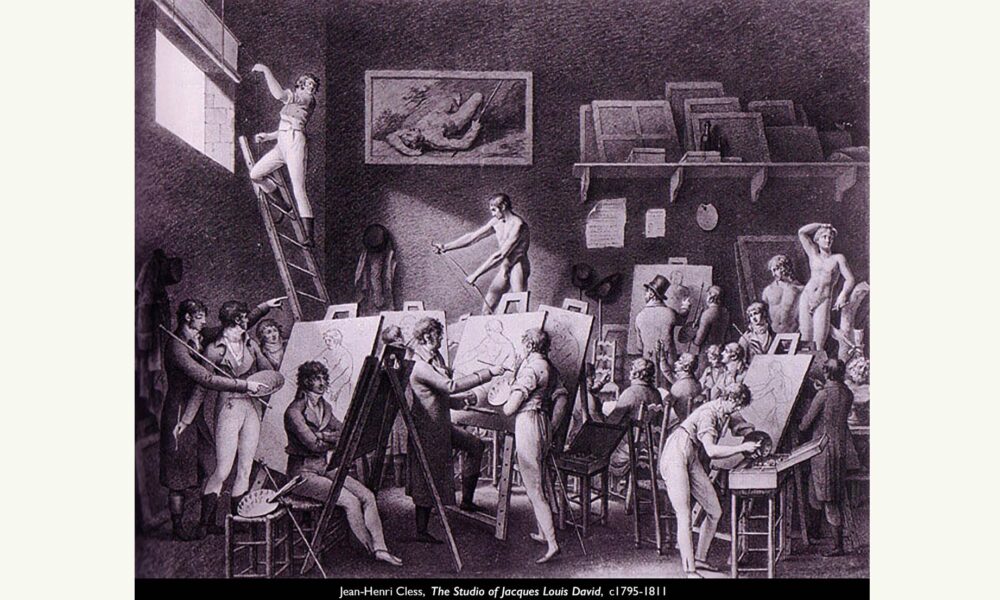

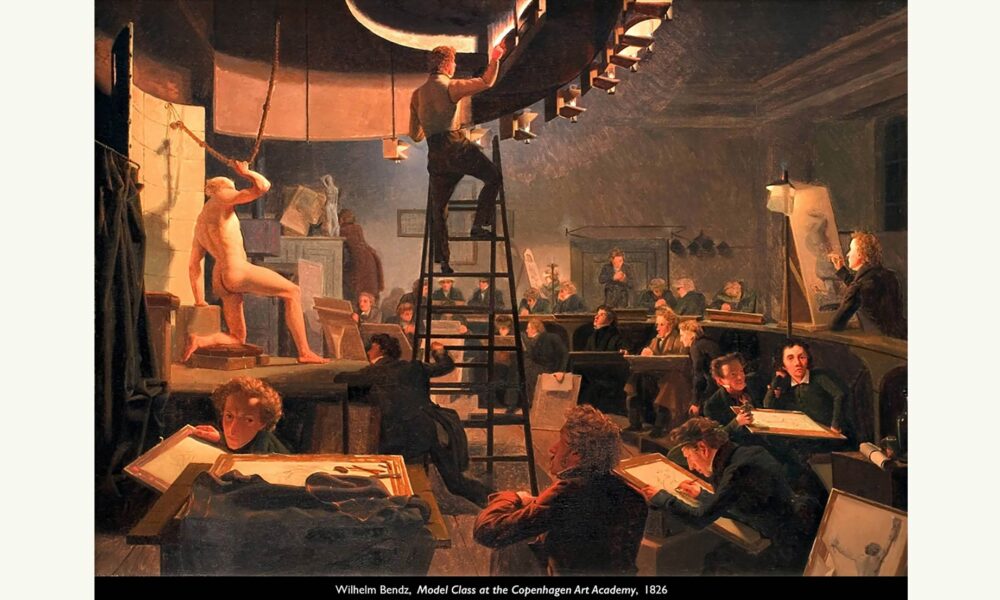

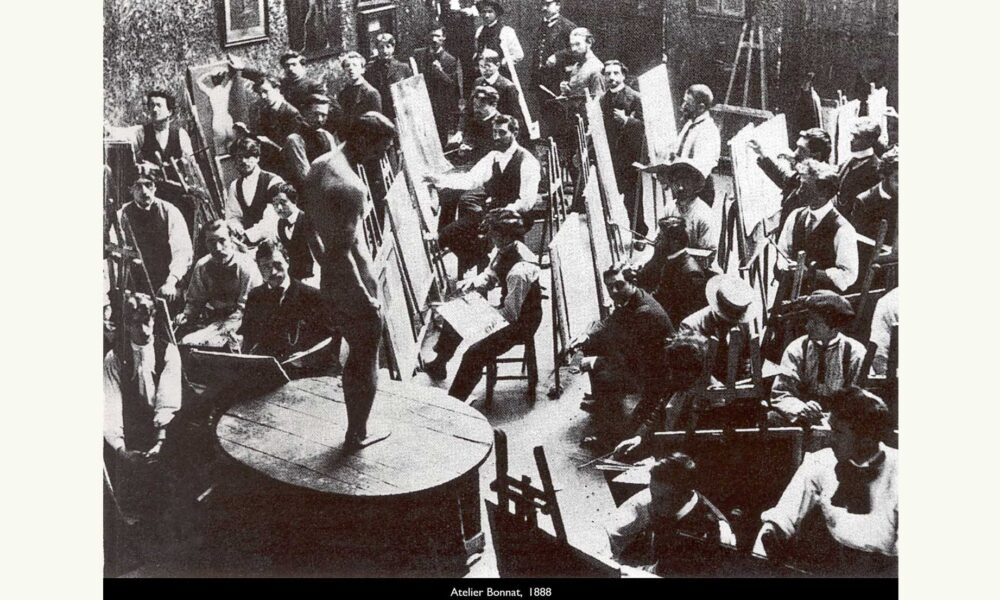

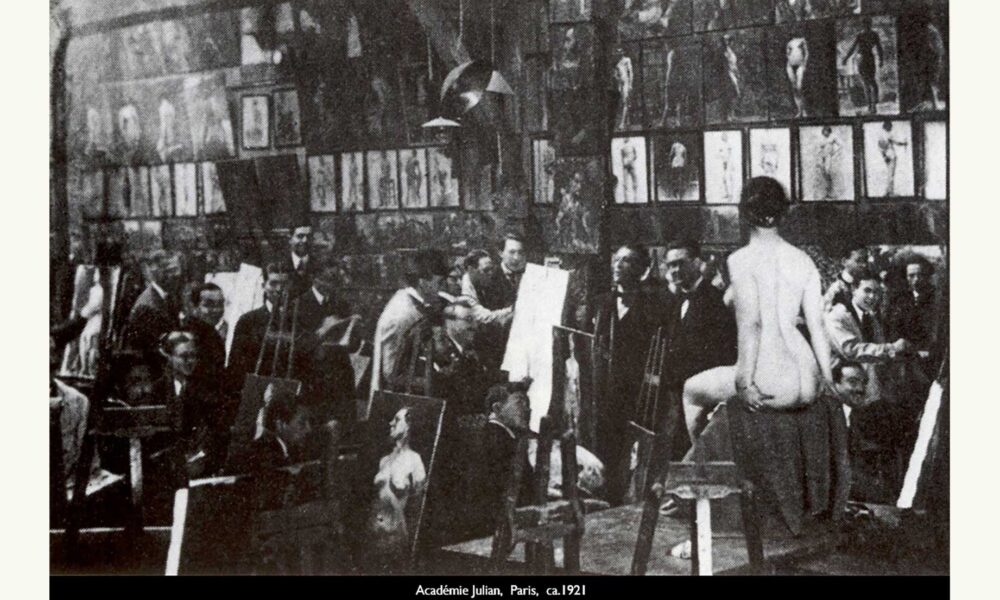

The sight-size method demands a very specific working environment and those conditions are easily recognizable (see the illustration above). The fact that one cannot find descriptions or images of working painters, draftsmen, students or apprentices prior to the last quarter of the 20th century using the sight-size method speaks volumes against its historical use. Simply look at any images of renaissance studios, 17th, 18th or 19th century ateliers, schools and academies and nowhere is there any evidence of the sight-size method. This is true whether the images depict figure work, portraiture, or cast drawing, and there are plentiful examples of each.

The question is then raised: if not sight-size, what method were these painters and students using? Unfortunately, even though historical images can show us that the sight-size method was not in use, they can not tell us precisely what drawing method is being depicted. However, there is one familiar method that is perfectly compatible with the historical images, namely, the comparative method of measurement. What is commonly known as the comparative method broadly encompasses any method of drawing that involves making measurements primarily using the naked eye, sometimes aided by a pencil, brush or plumb line, and comparing and contrasting these to some other reference or measurement within the subject. This comparison and contrast helps the artist determine correct proportions and geometric relationships. There is no transfer of measurements. Although different schools and masters throughout history certainly had their own particular style of teaching, their methods were still rooted in the principle of comparative measurement. One might say they were speaking the same language, but each with perhaps a slightly different accent.

The Positive Aspects of Sight-size

Many would say that the accurate images the sight-size method produces are its strongest positive feature, although others, like myself, would argue this point (see, Limitations). Two less questionable positive aspects of the sight-size method are that it is easy to teach and to learn. As mentioned above, the sight-size method is based on the careful and precise positioning of the model, artist and artwork in order to establish a fixed vantage point from which to view the subject and the artwork together. This fixed vantage point allows the instructor to see the model and the work-in-progress exactly as the student sees them, and therefore make objective judgments. Any drawing mistakes the instructor sees can be verified and corrected by the student simply by re-measuring. There is no subjective analysis involved, only objective measuring. This mechanical objectivity makes it possible for most students to grasp and learn the sight-size method with minimal trouble and also for anyone with a firm grasp of the method to teach it to someone else. Finally, the sight-size method has shown itself to be an effective means of teaching students how to discipline, or sharpen, their eyes over time to accurately perceive abstract shapes and relationships and make accurate visual comparisons and measurements.

The Limitations of the Sight-size method

In examining the negative aspects of the sight-size method, it will be useful to sometimes contrast it with the comparative method of drawing.

The sight-size method is limiting, by definition, because a sight-size drawing can only be exactly the same size as the subject as seen from a set position (“sight-size”). To create a sight-size drawing or painting of a subject much larger than life-size would involve having your easel far behind your subject and, conversely, to create a small sight-size drawing your easel would have to be a great distance in front of your subject. Both, though possible, are so impractical as to be pointless, and if attempted, would require an enormous amount of studio space. There are, of course, ways of enlarging and reducing drawings, but these involve a further mechanical effort. By contrast, the comparative method allows the artist to choose whatever size of drawing he or she desires, from any position and right from the start.

The sight-size method requires that the model and drawing board be placed so that they can be viewed side-by-side at a specific given distance. In the comparative method, the drawing board can be held in the artist’s hands, flat on the artist’s lap, or nearly any other conceivable angle in relation to the model and the distance from the model is never an issue (see the historical images above). Also, sight-size is only effective from at-or-near eye-level, whereas, the comparative method also allows you to draw a subject that is high above or below you, and even from your imagination.

Students who only learn the sight-size method are at a great practical disadvantage if they desire to work creatively and imaginatively because they are only familiar with drawing and painting what they can see and measure in front of them, next to their canvas. In other words, they are dependent upon their model and the ideal conditions necessary in which to work sight-size.

Another concern with sight-size is that aesthetic considerations are almost exclusively dependent on the actual appearance of the subject matter. At this point, it is important to acknowledge that the goals of the student are different from the goals of the mature artist. Whereas accurate and objective copying serves an important and valuable purpose in the early stages of a student’s training, it can be a handicap later in their career. People tend to act as they have learned, and students of sight-size tend to have a more difficult time shedding the tendency to merely copy the subject due to the specific mechanical system of measurement they have been taught to use. For many, copying the subject in such an objective mechanical fashion may be satisfying enough, but others have recognized in this a great fault and weakness. Sir Joshua Reynolds, the renowned painter and first president of London’s Royal Academy, wrote in 1770 that, “The first endeavours of a young painter, … must be employed in the attainment of mechanical dexterity, and confined to the mere imitation of the object before him,” but he went on to add “… students who, having passed through the initiatory exercises, are more advanced in the art, … must now be told that a mere copier of nature can never produce anything great; can never raise and enlarge the conceptions, or warm the heart of the spectator.”4 The greatly respected artist and teacher Harold Speed flatly states in his book, The Practice and Science of Drawing, which has long been a standard reference book for all students of traditional art, “Drawing, then, to be worthy of the name, must be more than what is called accurate.” Speed distinguishes between what he terms “scientific accuracy” and “artistic accuracy.” He states, “It is the difference between scientific accuracy and artistic accuracy that puzzles so many people. Science demands that phenomena be observed with the unemotional accuracy of a weighing machine, while artistic accuracy demands that things be observed by a sentient individual recording the sensations produced in him by the phenomena of life.”5 Sight-size does not allow for the artist to respond emotionally to the model in even the slightest degree, while the far less restrictive comparative method of drawing does. The sight-size method, to borrow Harold Speed’s words, is as unemotionally accurate as a weighing machine.

One might begin to wonder why the sight-size method is so popular and widely used considering its limitations. It is used, I believe, simply because the results are satisfying to so many, and because it is so easy to teach. By contrast, teachers of the comparative method work outside a clearly defined mechanical process and must rely more on knowledge and experience when training their students. Students of the comparative method are sometimes slower to reach the point of consistently accurate results because they are also working outside the safe and enclosed parameters of the mechanical, sight-size process, but reap greater benefits. Students of sight-size actually have to think less to achieve their results. For example, finding correct proportions, using the sight-size method, happens automatically. If the student using sight-size has measured and transferred points correctly, the drawing will be accurate in its proportions without the student even having thought about it. However, students drawing comparatively must find correct proportions by making numerous comparisons and corrections until the correct proportions are arrived at. What students of the comparative method ultimately gain by working this way, in addition to the ability to draw and paint accurately, is the ability to work independently, thoughtfully and naturally. That is in itself of immeasurable value to an artist.

All students, without exception, enter school with an almost desperate desire to improve their drawing skills. It is no surprise, then, that they are usually thrilled with the results of their sight-size efforts. Their drawings improve rapidly as they get more comfortable with the method and soon they may be consistently producing accurate, lifelike images. Their great satisfaction with this superficial accuracy can delay, sometimes forever, the realization that the mechanical method used to obtain those results is far more craft than art. Students of the sight-size method also risk forming the idea that a high degree of accuracy is a measure of success, or far worse, a measure of quality. Students need to understand and be constantly reminded that technical accuracy and the ability to precisely copy a subject is not art, but that those skills can be of great service to them on their path towards creating it.

It is important for everyone to appreciate that students and teachers using the comparative method are as concerned about accurate, faithful representation as those using the sight-size method, and that the results of the comparative method can be equally or even more accurate, in the technical sense, as results obtained using the sight-size method. It is only the path taken to achieve those results that differs. It is also worth noting, that it is certainly possible to make an inaccurate drawing using the sight-size method, and it happens regularly. The comparative road may be less clearly defined and more challenging, but it ultimately gives students greater options and flexibility to create their art. The ability to draw accurately is unquestionably important and should be mastered as a tool of expression, but not to the extent that one excludes or neglects artistic (aesthetic) accuracy. Frederic Lord Leighton, the great 19th-century painter and president of London’s Royal Academy for 18 years, beautifully expressed this in his first lecture to the academy. Leighton warned students of the danger of too much attention to technical accuracy in saying: “…an excessive absorption of the attention in the most superficial aspect of things tends to the over-development of the simply imitative faculty, which is the lowest gift of the artist, at the cost of his aesthetic faculty and of his imagination, which are the noblest, and tends therefore also to triviality and loss of that which gives to Art its high place amongst the elements of civilization.”

Conclusion

Since students using the comparative method can obtain results that match or surpass the results obtained using the sight-size method, I see no reason to recommend the sight-size method. Naturally, students trained using the sight-size method can go on to become accomplished and successful artists, as can students of other training backgrounds. The important question is whether or not sight-size is the best way to start students on that journey. I do not believe it is, and moreover, I think it can be a hindrance to them. The limitations of the sight-size method and risks to the student’s development as a creative artist, in my opinion, clearly outweigh its positive aspects.

It is worth noting that the greatest and most admired examples of realistic art, which hang in museums across the world, were created by people who had no knowledge of the sight-size method. They did not need it and surely we do not either. However, I am not a purist in that sense. I believe that there are many effective ways to teach students to draw and paint realistically, and that some of those methods are being developed today and others are yet to come. At best, sight-size may be suitable for training beginners to see and render objects accurately, but students must soon be weaned from the method or they risk becoming far too reliant upon it and consequently lose confidence in their ability to work outside of its strict limitations. In fact, because it is such an unnatural way to draw, many students of the sight-size method eventually find themselves drifting toward the more instinctive comparative method on their own, which can be a difficult and confusing process. If sight-size is ever going to be taught at all, it should be taught in conjunction with the comparative method, in order to make that transition more smooth and comfortable. Many teachers of the sight-size method do not even use the method themselves in their personal work – most not at all – and they often come up with elaborate explanations to justify the hypocrisy. It would be more honest if they simply accepted their abandonment of the method as evidence that the sight-size method is not, ultimately, a natural, practical, or very satisfying way to draw or paint. I hope they might also consider how much better it would be for students if from the beginning, students received proper training in the comparative method by knowledgeable and experienced instructors, or at the very least, could be helped to make the transition from sight-size to the comparative method at a suitable point in their training.

The Role Measuring has Within the Definition of Sight-size

The internet has millions of references to sight-size, and one does not need to explore them all before something becomes clear: there is a common perception that sight-size is about, or closely associated with, measurement – whether it is described as a system of measurement, or simply as setting up one’s work environment to facilitate and simplify measuring (or comparing) the subject to the artwork.

While those people who believe that sight-size is not defined by measuring may be united in their opinion of what sight-size is not, they do not provide a specific, thorough or consistent definition of what sight-size is.

On a website exclusively devoted to sight-size, Darren R. Rousar, author of a book on sight-size, addresses what he believes are some misconceptions regarding sight-size. There he quotes individuals who are intimately connected to sight-size and largely responsible for its widespread use. Mr. Rousar intends these quotes to help disprove the idea that sight-size is based on mechanical measuring, but admits, “this misconception seems difficult to refute due to how Sight-Size is commonly taught.”6 However, instead of lending support to the idea that sight-size has little or nothing to do with mechanical measuring, their words only add to the confusion. For example, Richard Lack is quoted as saying, “Measuring can be a part of Sight-Size but it is not its definition. Measuring is to Sight-Size as scales are to a violinist. Playing the violin is not defined by practicing scales, neither is Sight-Size defined by measuring.”6 Unfortunately, we are left to wonder what Mr. Lack’s definition of sight-size is. I would agree with Mr. Lack that the violin is not defined by practicing scales, however, learning and understanding the scales is a necessary condition of playing the violin, which would suggest, based on his words, that measuring is a necessary condition for executing sight-size. Measuring, therefore, is not optional and so certainly a part of its definition, at the very least. Charles H. Cecil states that, “When properly understood, sight-size is not a mere measuring technique, but a philosophy of seeing.”6 Mr. Cecil here acknowledges that sight-size is a measuring technique, but adds that it is also more than that, namely, “a philosophy of seeing.” Again, we are left to wonder what exactly that means. Mr. Rousar states that, “Most ateliers that teach Sight-Size do so by incorporating measuring into the approach. My book, Cast Drawing Using the Sight-Size Approach, is no exception.”6 From these quotes it is quite obvious that measuring is involved with sight-size. However, Mr. Rousar also quotes two other individuals who provide their own definitions of sight-size that suggest otherwise. Richard Whitney could not be clearer when he states, “Sight-size is the visual placement of the canvas, subject and artist only. Measuring (though very helpful) has nothing to do with sight-size.”6 Robert Douglas Hunter defines sight-size in this way: “Basically, it is a method of viewing the model and your painting simultaneously from a selected position so that both images appear the same size.”6 Mr. Hunter’s definition is in keeping with Mr. Whitney’s, but it also gives us a bit more detail, including why the term “sight-size” is so fitting to describe the method. The common thread within these diverse descriptions is that the image the artist creates is the same size as he sees it from a specific position. This is echoed on Mr. Cecil’s website where he states that his school teaches the sight-size technique, meaning that the “subject and image are depicted to scale as seen from a given distance.”7 The sight-size website itself defines sight-size as, “a way of seeing and comparing nature to your drawing, painting or sculpture from a given distance. Using Sight-Size, the size you see the subject is the size you draw, paint or sculpt it.”8

These quotes and descriptions do not help to clarify the role of measurement within sight-size, but confuse the issue. It is clear that some individuals quoted by Mr. Rousar whose opinions we are clearly meant to respect, understand that measuring is involved with sight size, but then another absolutely denies it, and shifts the focus to the placement of key elements, a factor which is echoed again by someone else.

If one thing becomes clear, it is that the definition of sight-size is quite unclear; at least among those people who would like us to think that sight-size has nothing to do with measuring and much, or perhaps everything, to do with the placement of the artist, subject and canvas. If Mr. Whitney is correct in saying that sight-size is only about placement of canvas subject and artist, then there isn’t much to discuss. Of course, in that case there isn’t much to teach students either – simply set them up properly and tell them to start drawing. But it certainly isn’t that simple. Mr. Rousar, himself, states that, “Training one’s eye using Sight-Size is a long and involved process.”6 That would not be true if sight-size was only about the placement of the artist, subject and canvas. What takes time is that students need to be taught how to look at nature, organize, and then record the information they are seeing upon their canvas. This involves measuring because the simple act of seeing, or looking at a subject, especially in the context of painting or drawing, involves measuring.

If it can now be agreed that measurement is at least a part of the sight-size method, if not at the heart of its definition, then the important question is what kind of measurement is involved? Here, too, the issue is confusing. The fact is, proponents of sight-size train beginners in the method using mechanical measuring techniques taught in a very specific manner (as described by Peter Bougie in his essay1 ), but then suggest that at some point all that changes. When or how is not made clear, only that, as Mr. Rousar states, “a fully trained artist who uses Sight-Size might never use a plumb line or even consciously think about literal measuring.”6

All of this confusion and contradiction seems to boil down to the following problem: The desire to separate the specific mechanical measuring process that is used to teach students the sight-size method from how those students often end up working as mature painters. As sight-size proponents describe them, these are clearly very different situations, yet they still insist on calling them by the same term. Students of sight-size measure in a rigid mechanical fashion, but not all continue to use that measuring process as mature painters. After years of sight-size training, some key elements of the method, such as visualizing the subject through a horizontal/vertical grid, might be internalized, and there is no need to physically take and transfer measurements. At this stage, other ways of measuring the subject may seem more natural and intuitive.

Sightsize.com says, “Any artist who draws, paints or sculpts with the work visually next to their subject may be practicing Sight-Size,”8 but this statement also suggests that the artist may be doing something else, such as practicing comparative measurement. Even the descriptions of sight-size on the sight-size website begin to sound very much like the comparative method: “the proper definition of Sight-Size must use the broadest definition of measuring. Measuring not only means ascertaining the length or width of something, it also means comparing the look or impression (comparing being the important word here).”8 Sight-size proponents seem to want to make their definition of the sight-size method broad enough, or vague enough, to encompass both the mechanical sight-size measuring system used to train students and the comparative method. What is evidently happening, is that as fully trained artists, these sight-size proponents have cast off the mechanical sight-size measuring technique and are actually practicing the comparative method of measurement – but steadfastly insist on calling it “sight-size.”

As far as the placement of the canvas, subject and artist is concerned, the definition of sight-size must include more than only this. It also needs to include the fact that the image created must be exactly the same size as the subject as seen by the artist from a given position (“sight-size”). Placing the canvas next to the subject and stepping back to compare the two is not a complete or exclusive definition of sight-size, because it also includes the comparative method. A fair definition of sight-size could be: When an artist places his or her canvas next to their subject so that the image the artist creates, with the aid of mechanically obtained and transferred measurements, is exactly the same size as the subject appears to the artist from a specific vantage point. The definition of sight-size must include reference to mechanically obtained and transferred measurements, because that is how the image is created. If an image is created by obtaining measurements using the comparative method, even if it is exactly the same size as the subject from a specific vantage point, it would be wrong to call it sight-size. Naturally, the word “sight-size” would be a logical and suitable adjective in such a case, but unfortunately it carries with it too strong associations to the mechanical measuring system of the same name.

We need to recognize the difference between the methods. This is important because the sight-size method substitutes a human machine – a craftsman in tightly controlled circumstances who mechanically measures and transfers those measurements to form an image – for a sentient individual artist making judgments and comparisons to form an image (the comparative method). Personally, I would never want anyone to think that I am working sight-size in similar circumstances, because I understand what sight-size is and would frankly feel it insulted my skills and ability, and there are many others who feel the same way.

As stated before, Mr. Whitney’s definition of sight-size – namely, that it is the placement of canvas, subject and artist only – leaves us with no method, technique, or system to teach students. In fact, it would not be worth mentioning sight-size as part of any training curriculum if that was all there was to it. Clearly, this is not the reality we know. Even sight-size advocates and enthusiasts admit that students are taught sight-size in a very specific fashion using a rigid mechanical measuring technique.

I have no issue with the placement of canvas, artist or subject. I only take issue with how students are taught to measure (in other words, to analyze their subject) using the sight-size method. I take issue because I know there is a better, traditional, less limiting and more natural way to teach students to draw any subject, from any position and in any size, with results equal to or superior to the sight-size method. That method is the comparative method.

© Hans-Peter Szameit, 2008-2024, Co-Founder, Director, Instructor- Charles Bargue, with the collaboration of Jean-Léon Gérôme: Drawing Course. By Gerald M. Ackerman, Published by ACR Edition Internationale. See, Appendix 2: The Sight-Size Technique. Interestingly, although Bargue’s beautiful plates reproduced in this book are used extensively by most schools that teach the sight-size method, the plates show that they were originally intended for use with a method other than sight-size, based on the blocked in drawings that accompany many of the finished drawings. Bargue’s use of slanting lines – even curved lines – to indicate important relationships within the subject are not in harmony with the rigid horizontal/vertical grid approach of the sight-size method.

- Mr. Beer kindly informed me that he re-titled his essay some years ago, changing the title to “The Sight-size Portrait Tradition”, but one still finds frequent reference to it by it’s original title.

- Charles Bargue, with the collaboration of Jean-Léon Gérôme: Drawing Course. By Gerald M. Ackerman, Published by ACR Edition Internationale. See note 82.

- Discourses on Art, Discourse III

- Pages 35-36

- www.sightsize.com/misconceptions.html (May 2009)

- www.charlescecilstudios.com/html/philosophy/atelierTradition.html (April 2009)

- www.sightsize.com/history.html (May 2009)

Download the essay in PDF format:

The Comparative Method vs. the Sight-size Method